Beauty as Criterion for Art

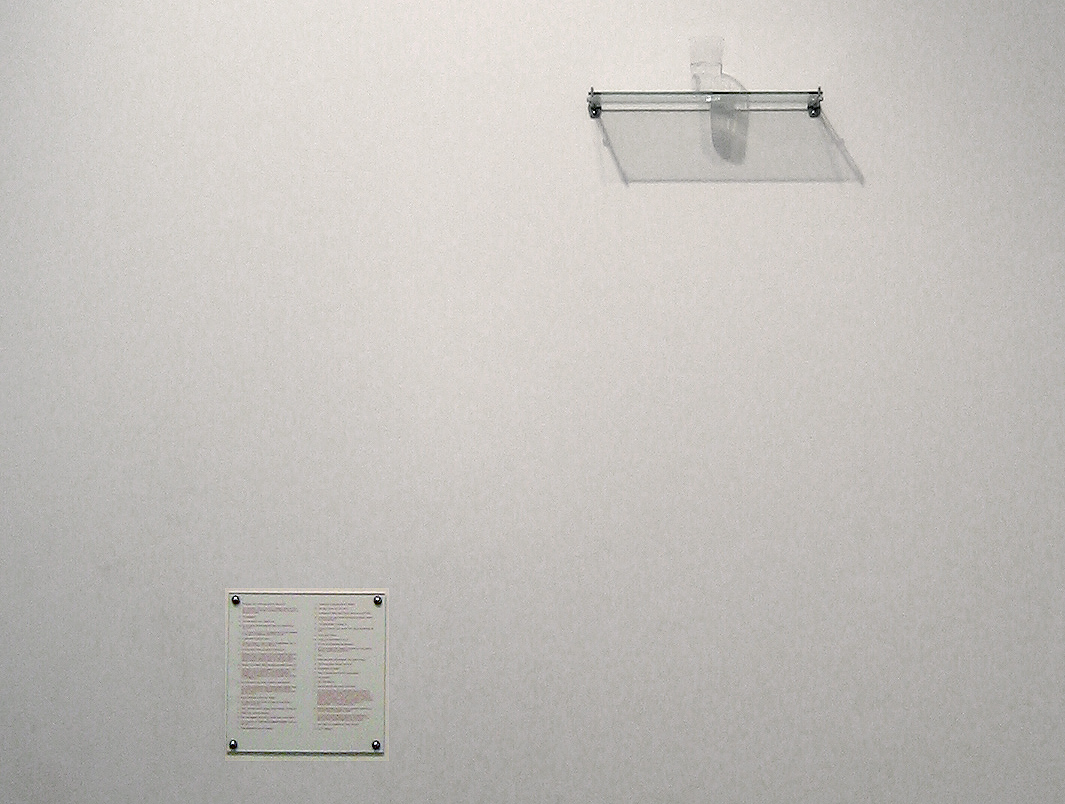

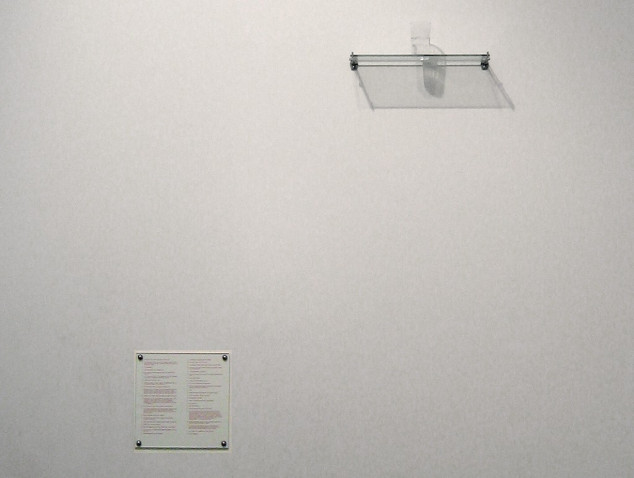

Oak Tree by Michael Craig-Martin installed in the Tate Museum in London. Taken September 2005 by Jim Harper

A sunrise. The end of a disney movie. The mountains. A towering chrome building. A painting. The face of your lover. A poem.

Often, these sorts of things would be considered “beautiful,” possessing some sort of aesthetic pleasurability that almost implies or touches upon The Divine. Beauty, colloquially, is often considered a positive quality, desirable, inherently good.

But what is Beauty? How is it discussed in the art world today? Do artists care about things being Beautiful? Should they?

Well, let’s look at some of the examples in the last fifty years of art:

An Oak Tree, by Michael Craig-Martin, 1973: a glass of water on a high shelf, along with a Q&A formatted textual piece explaining why the glass of water is actually an oak tree….

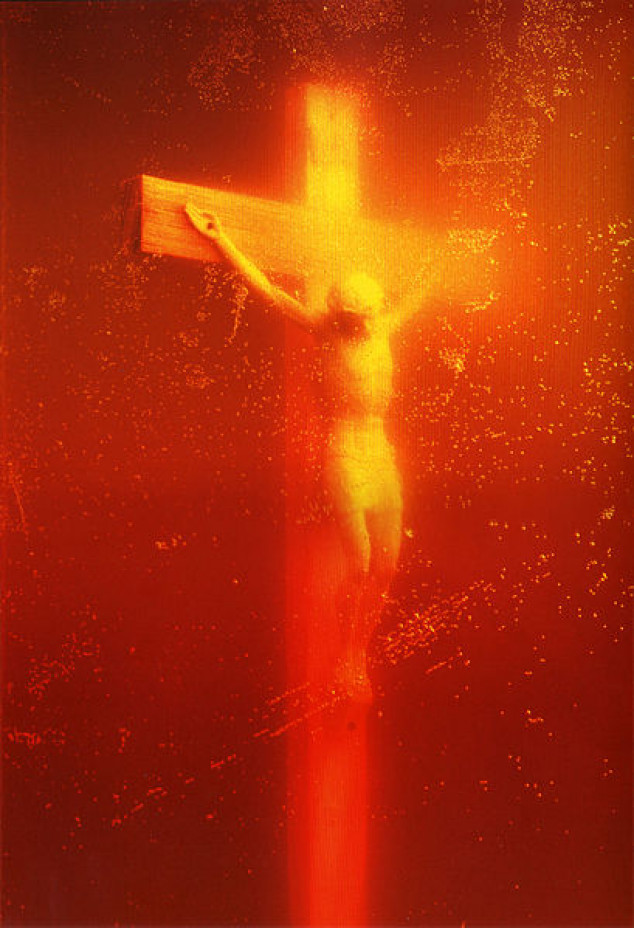

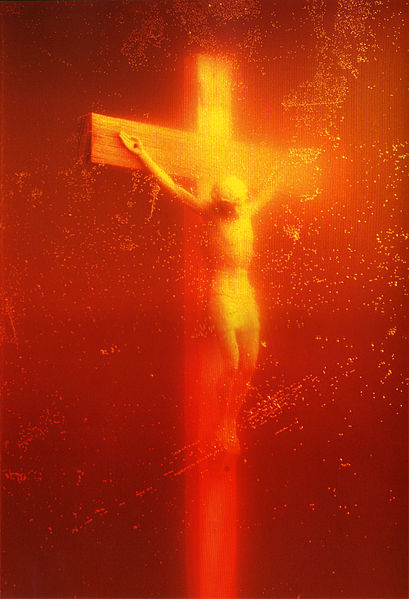

A 1987 photograph by Andres Serreno, wherein a crucifix is submerged in a container of the artist’s own urine…

The Lights Going On and Off, a 2001 work by Martin Creed, featuring an empty room in which the lights go on and off…

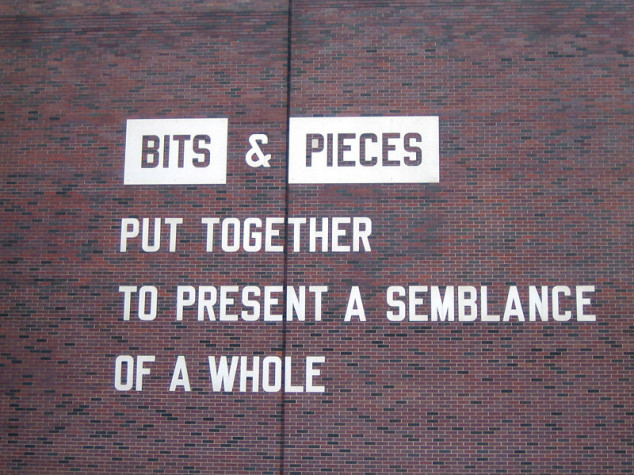

2005: Bits & Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole, a work by Lawrence Weiner literally consisting of the text “BITS & PIECES PUT TOGETHER TO PRESENT A SEMBLANCE OF A WHOLE”…

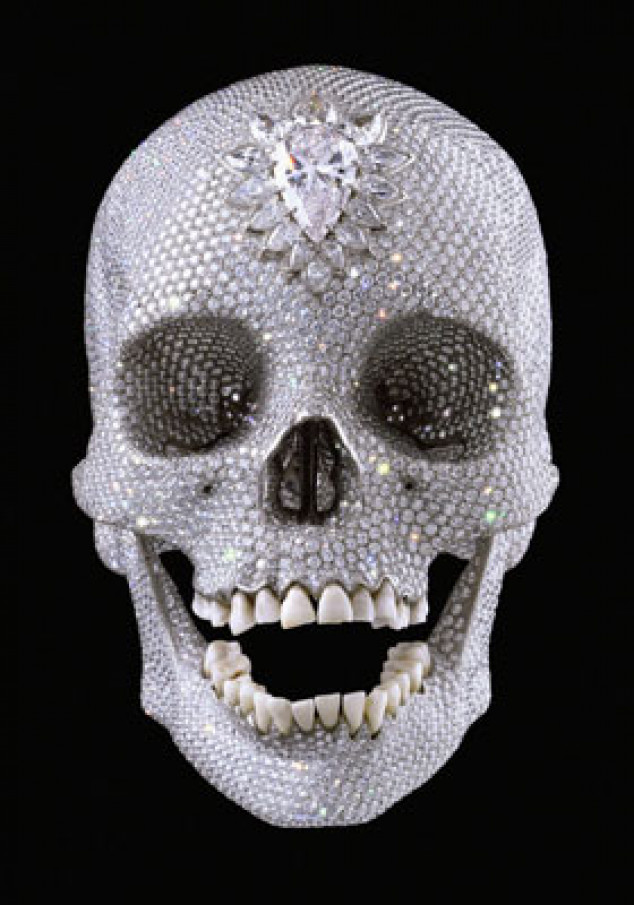

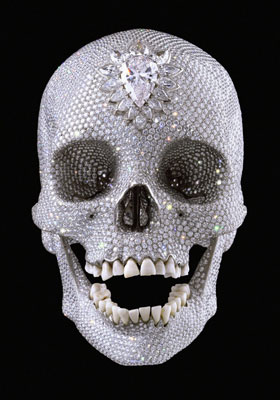

For the Love of God, made in 2007 by Damien Hirst. Consisting of a gaudy platinum skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds, more like an gaudy piece of opulence than a serious artwork, sold for fifty million british pounds…

At first glance, these works seem to give the impression that, in the modern art world, the general consensus about the question of beauty as a valid criterion for art is a resounding “No.” That somehow, in this modern day and age, Beauty is irrelevant to the nature of art and, in some cases, has no place in it.

Photograph of “Bits & Pieces Put Together To Present A Semblance of a Whole” by Lawrence Weiner on display at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota

For the last fifty years, modern art world, it seems, has an emphasis on the intellectual over the spiritual, the mind-engaging over the mind-expanding– a trend fully realised through the entire genre of Conceptual Art: art focused not on the visual nor aesthetic nor beautiful, but entirely on the concepts employed in the work, works like An Oak Tree or One and Three Chairs. Ideas have become more important than craft–Damien Hirst employs individuals to do his art for him, commercialises and commodifies his artistic persona.

And this isn’t me simply picking out some of the stranger trends in the art world– this sort of thing is common in today’s art market. Erased drawings of other people hung up in art galleries. Books of instructions to create art. Musical scores consisting entirely of silence.

Now, there isn’t anything wrong with this kind of art, per sey, and these works really are legitimately engaging and potentially powerful artworks that discuss the nature of important concepts, but something is missing. Something spiritual, something inherently noble: namely, they are missing the quest for Beauty

Now, this is fine for the Art in the first-rate; this kind of art manages to be Beautiful without even trying to pursue it, but when this sort of Postmodern pursuit for “avant-garde” intellectual engagement reaches third- or fourth-rate artists, we get the repetitive work of copycats that fail to create something legitimately personal, lacking any sort of beauty or invention. Sub-par works of performance art body horror shock tactics etcetera turning off the entire world to the legitimacy and vibrancy of the art world.

“In Ancient Greece, the artist’s job was to find the ideal,” said Sean Oswald, art teacher at Talawanda. “Now, in our culture filled with only conceptual artists, all we’re getting is ideas, poorly executed.”

So, the inevitable question: what has become the new criterion for artistic ability in the art world?

Oswald says the new criterion has become novelty. “The driving force in the art world is trying to outdo each other, novelty is king, novelty is God.”

Further, the art world has fallen into the pocket of academic circles. “[Academia] has taken the conversation from the actual artists,” Oswald continued.

Not only, that, but Art is in the service of the Art Market, of billionaire buyers and “tends” in art sales. Damien hirst has a team of artists make his dot painting for him for a reason. Art used to be like literature, but now it’s become more like the vain world of fashion. Only the marketable, tabloid-eqsue artists are getting attention from buyers, galleries, and the media. Beauty has stopped being part of the conversation about art because those willing to discuss those ideas have been shut out of the artistic dialogue. This type of nonsense is why the everyday person thinks the art world is a bunch of pretentious nonsense: because, for the most part, it is.

But then there’s the reverse problem, the one the stereotypical postmodernist raises when confront with the Problem of Beauty: “What really is beauty, anyway?”

This, really, is the heart of the problem. The postmodernist says “everything is beauty!” and therefore forsakes the concept entirely, while merely a little over a century ago, the problem was one of too strict of a definition.

That is, in the late 19th and early 20th century, in the infant stages of modernism, the “old world” of art was still very much an institution of power. The popular cultural paradigm of the time informed people what was “good” or “bad” art. These were institutions that were thousands of years old, had birthed generations upon generations of renowned artists. The old world of media had power, cultural power. And, in most regards, it was very conservative with what it considered “art.”

To put it bluntly, they used the idea of beauty in art as a cultural weapon, a blunt instrument to bash away other aesthetic considerations of the world. It was that paradigm that the modernists had to fight, with cubism and surrealism, readymades, new mediums, new ideas, intentionally subverting all the expectations of beauty and art that existed in that time’s cultural consciousness.

And that’s the thing: that trend continued, the art world continually trying to subvert itself, distance itself infinitely from the art academies and Romantic masters, subverting art technique, message, form, and ideals, flowering into the cultural paradigm of postmodernism in the sixties, until finally becoming so subversive that the shock-horror nonsense that the art world serves to itself could literally be feces on a canvas.

That isn’t beautiful. There’s a place for ugly in art, but not like this, not this glorification of literal decay, not without and pursuit for the sublime and beautiful.

Cue the postmodernist sneer: “You don’t get to decide what counts as beautiful.” You’re right. I don’t. Neither do you. Each of us, individually, chooses what is truly beautiful.

So, no, I can’t demand preconceptions of what is beautiful to be changed. But I can ask to pull back the facade of pretension, of only half-executed ideas, of an art culture that values ideas instead of hard work, I can ask that the artist not delude themselves in the nonsense of their own ids and egos, that art starts being about pursuing beauty and truth and expression instead of pervertedly exhibiting the inane and self-obsessed.

In this regard, we need to look to the Impressionists and Modernists and their works, despite being strange works fueled by ideas, still represent a continual pursuit for beauty and truth: Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Picasso’s Guernica, Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass– all of these works look deeper, search further, and burn brighter than the empty pretension present in our galleries today.

Art is about searching for beauty, about finding it and figuring it out, about displaying honest human emotion back to us. That isn’t trite. That isn’t banal. That isn’t limiting. The pursuit for beauty and truth, that infinite spiritual work bestowed upon everyone who must create, is a personal quest equal parts spiritual, emotional, and intellectual. To inflate any one of these qualities more than the other two is create an art culture full of the fleeting and dumb, soulless, wandering works destined to disappear a thousand years from now.

A very fitting article!

Really nice article!